Researchers at the University of New Hampshire have developed a new method of measuring the impact of marine heatwaves to provide more detailed assessments on how they impact sea life.

The research, published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, reviewed how researchers can better approach and understand the impacts of marine heatwaves and calculate the survival rate of marine organisms. Researchers said the new methods are needed as marine heatwaves become more common amid climate change.

"Traditional statistical methods fall short because they ignore the biological responses of organisms,” Easton White, a scientist with the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station, said. “Our physiological framework, which we present in this paper, considers how marine organisms respond to both the intensity and duration of heat stress, offering a much clearer understanding of the lethal impacts of marine heatwaves.”

Marine heatwaves have already documented effects on marine life that has directly impacted the seafood industry.

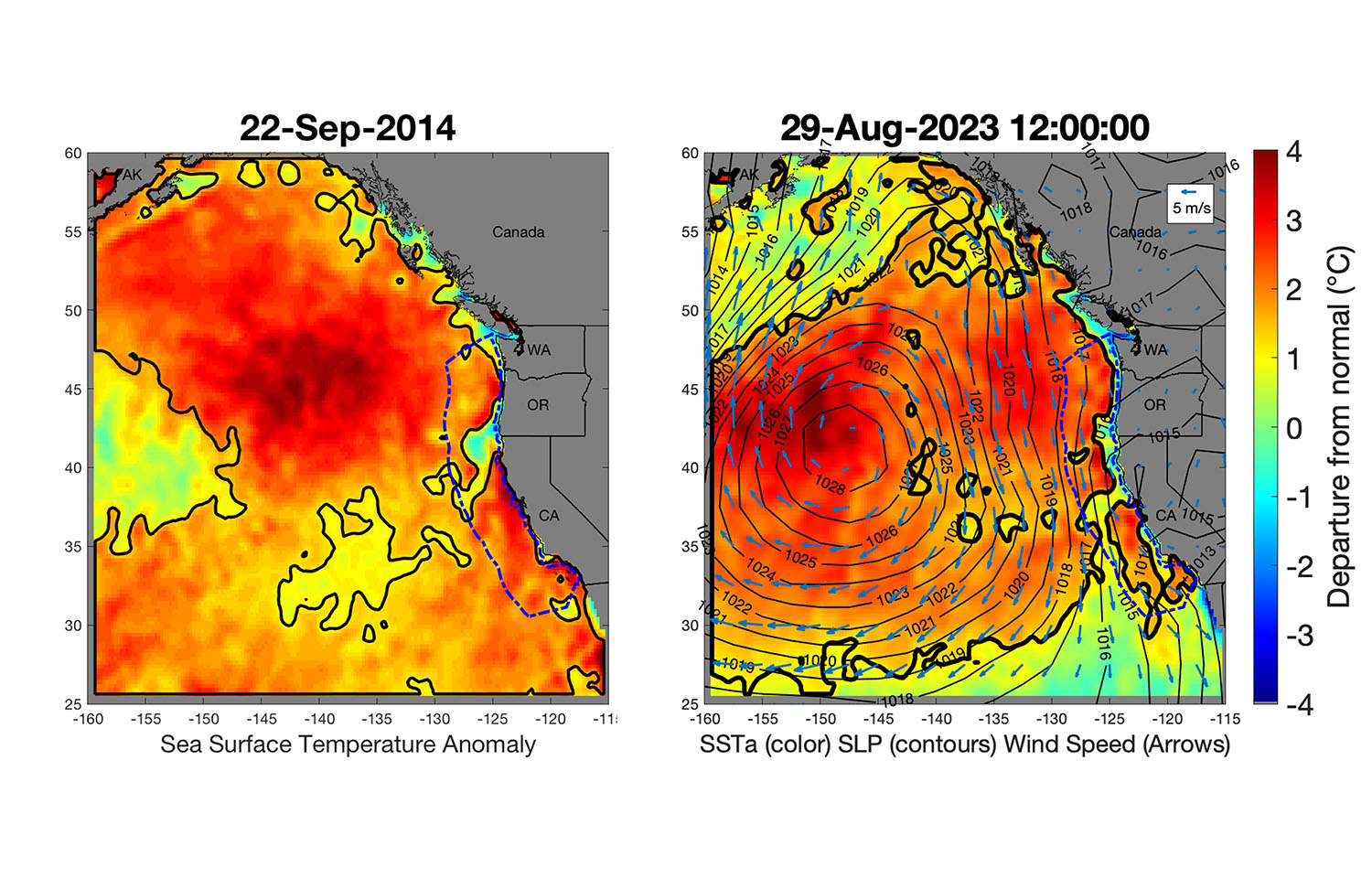

A marine heatwave known as the “blob,” which hit the Northeast Pacific Ocean in 2019, impacted seafood stocks in Alaska’s Bering Sea. The blob had severe negative consequences for some commercial fisheries, and research showed the heatwave was responsible for a sharp decline in Bering Sea snow crab that forced regulators to close the fishery for the 2022-2023 season.

White said the new research and strategy could be crucial for predicting what impacts marine heatwaves will have and mitigating the effects.

"By understanding the specific survival thresholds for different marine species, our research can provide insight into how various heatwave profiles impact marine life," Andrew Villeneuve, a Ph.D. student at UNH’s marine biology program, said. "This understanding is key for developing more effective conservation and management strategies to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems."

The researchers examined both acute marine heatwaves – where there was a sharp spike in temperature for a short time – and longer-term, chronic heat events. Through the research, they identified instances where the impacts of both long-term heatwaves and shorter-term, higher-temperature heatwaves overlapped.

“While most research attention has focused on chronic marine heatwave events, we show similar lethal effects can be experienced by more common but neglected acute marine heat spikes,” the researchers wrote. “Critically, a statistical definition of marine heatwaves does not accurately categorize biological mortality.”

Understanding the heatwaves will help researchers and scientists better react, the researchers said.

“For instance, if a specific marine species is found to be highly susceptible to short, intense heatwaves, conservation measures might focus on creating refuges or cooler microhabitats during these peak heat periods to help ensure their survival,” Villeneuve said.